The Twiss Family Birdhill

Twiss’s Hill is one of the best known landmarks in the Birdhill area, but have we ever stopped to ponder on the Twiss name and its origin. For most of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Twiss family was the principal landowner in Birdhill. The only remnants of the family still visible in the district are the ruins of the dwelling which overlooks the N7 between the village and the church, and the grave of Bob Twiss, railed and concreted at the top of Chapel Hill. Such remnants belie a once beautiful and impressive house and surroundings and a family which was widely respected

Birdhill House, home of the Twiss Family, c 1877

The Twiss family first settled in Ireland during the reign of Charles 1, when a Richard Twiss living in Kilintierna, Castleisland, was a J.P. of Kerry. One of his descendants, Robert (1777-1851) who married Elizabeth Atkins in 1804 was also J.P. and High Sheriff of Kerry. The Atkins were originally from Firville, Co Cork, but had inherited the property of Stephen Hastings at Forthenry near Ballina. Another Atkins daughter, Margaret, married Arthur Ormsby, who lived in Courtwood, Birdhill. Courtwood was situated adjacent to the old Kyle graveyard. The Ormsby estate took in most of the parish of Birdhill.

Firville House, near Mallow as it is today

In 1824 the Ormsbys opened a Bible School and requested all the children on the estate to attend. The parish priest, Rev James Healy, forbade the children to attend and as a result, Ormsby issued an eviction decree to his tenants dated 29th September 1827. Some 20 families were served with notices. Fr. Healy wrote to the Catholic Association for financial assistance for the unfortunate victims who were now homeless and in great distress. The total number evicted was 128, counting wives, children, dependants and relatives – included were James Walsh, Thomas Dowling, Michael Burke, John Kennedy, William Condon and William Kirby. £60 was received from the Catholic Association in Clonmel in May 1828 and £5 came from a Lancashire Catholic who had read about the Birdhill eviction in the Tipperary Free Press. The issue was the topic of numerous letters in local and national papers.

Margaret Ormsby survived her husband but moved to Cork when Courtwood was burned down. She left her estate to her nephew, George Twiss (born 1807). George was also successor to his father Robert’s estate at Parteen House. Shortly after his aunt’s departure, George moved from Parteen to Birdhill House in which the Atkins family had also lived from about 1824 to 1840.

The lands of Birdhill had many and varied owners down the years. The Lynches, chiefs of Cragg, had ownership up to about 1,000. The Donegans held sway to 1,300, when the O’Briens of Arra took over. They built the first castle in Birdhill in the fourteenth century. The castle was on the same site on which Birdhill House later stood. After the rebellion of 1641 the land was granted to Lieut. William Sheldon, a Cromwellian Officer. In 1790 the Goings came to Cragg House and ten years later they acquired the lands of Birdhill. They remained the landed family until 1825 when Arthur Ormsby was listed as the registered owner.

George Twiss (1807-’78), who inherited the lands of Birdhill from Margaret Ormsby, was unmarried. A letter written by his sister in 1877 notes that he was ‘a little soft in the head.’ In fact, a rent slip from 1878 refers to ‘George Twiss a lunatic.’ George found himself at the centre of controversy in 1848. In March of that year, the lease for the Catholic Church was up.

Twiss wrote to Fr. Redmond Burke P.P. and to Archbishop Slattery (addressing him as Sir), but he got no reply from either. Twiss was willing to renew the lease under certain conditions – no other building on the church grounds and the church to be used for Roman Catholic worship only. At that time churches were often used for many and diverse purposes. Grain was often stored in them and political meetings held there. The Blessed Sacrament was not kept in the church in those days. The priest had no parochial house and so they travelled around living with the people. As they carried the Blessed Sacrament with them, the custom of raising the hand or tipping the cap to the priest originated. The fact that they stayed in the houses of the parishioners gave rise to the ‘stations’ where mass was celebrated in local houses for the people of the neighbourhood. Twiss wanted a legal deed drawn up incorporating his conditions for renewing the lease. Fr. Burke would not agree. A notice was placed on the door proclaiming ‘This Church Closed.’ When the priest came to celebrate Mass on Palm Sunday he had to move to a nearby house. Twiss eventually signed over the chapel at a nominal rent of one shilling.

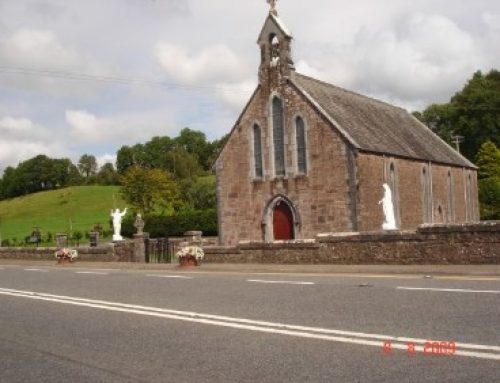

The church referred to above stood on top of the Chapel Hill. It fell down in 1860 and Mass was said for the next ten years in one of Coffey’s houses nearby. There were difficulties in acquiring a site for a new church. George Twiss was reluctant to give any land for this purpose but he eventually agreed to give a small pond, which was soon filled in and it was there that the present church was built in 1871 at a cost of £1,200.

George Twiss died in 1878 and all his tenants were ordered to attend the funeral. His body was taken to O’Briensbridge and carried into the Protestant church by his Catholic tenants. During the service some of the tenants were observed to be engaged in talking and laughter. The service was stopped and they were removed, but they had got their wish – being reluctant participants in a Protestant service.

George was succeeded as landlord by his brother Hastings (1817 – 1897) who was at the centre of a much publicised boycott in August 1881. The Boycott System first used against Captain Boycott of Lough Mask House, Mayo, was introduced by the Tenants Rights League in an effort to improve the lot of tenants. In 1881 the Twiss estate was in financial difficulties and when the receiver, a Mr. Richard R Studdert, took action against the tenants for unpaid rent, the local Land League branch put a boycott on Twiss. A problem arose when the large tract of meadowing at the Polloughs became ready for harvesting. The normal practice was to sell the hay uncut to the local farmers and then to rent some of the after-grass to them. Now his farmer customers were not allowed deal with Twiss because of the boycott. Neither could Twiss secure local labour to harvest the crop himself. The only alternative was to apply to the Property Defence Association for a workforce to do the job. For this service he was to pay £1.5s.5d. an acre.

On August 8th 1881 an expedition of 70 labourers with 3 gentlemen in charge arrived by train in Birdhill, their purpose to cut and save 700 acres of hay valued at £2,500. They brought with them 4 mowing machines, 4 hay ladders, horse rakes, 13 horses. Provisions brought included preserved meats, bacon, 200 loaves of bread, several barrels of Guinness and a quantity of oatmeal. These ‘Emergency Men’ camped in the ‘Bang Up’ (beside Matt the Threshers). The possibility of a confrontation was avoided by the presence of a large contingent of police and military who patrolled the roads day and night during the four weeks it took to get the work done.

Hastings Twiss died aged 80 years on 16th September 1897 and lies buried with his wife Sarah (died 1906) in St. John’s, Newport. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Robert George Edward. Robert (Bob) was born in 1856 and served in the Afghan campaigns of 1870-80. He married Elizabeth Drake (Shinrone) but had no family. He was High Sheriff of Tipperary in 1896 and was a member of the Grand Jury of the North Riding for many years. He died in 1917. It was his wish to be buried in the local Catholic graveyard but Canon Howard would not allow it. He even promised to give a site for a new cemetery but to no avail. Consequently he was buried on his own land on the hill behind the church.

The grave of Bob Twiss can be seen from the road at the top of Chapel Hill

Locals say that his dog, medals and valuables were buried with him. It was rumoured that attempts were to be made to dig up the grave to get the valuables, but Joe Greene, agent for the estate had it covered with cement to a depth of six feet. Bob’s wife survived him but returned to her home place after his death. His nephew, Bobby Thomas, son of Alexander Thomas, Rector of Nenagh, succeeded as landlord of the estate. When the War of Independence broke out, the Twiss family went to England for fear of attack. The house was burned in 1920 and never rebuilt. Compensation of £40,000 was allowed, provided that portion of it be expended locally. Bob’s wife, Elizabeth, ordered that £10,000 be spent in building a terrace of 9 houses at Church Road, Nenagh. These were finished in 1927 and the clergy of Nenagh still reside in some of them.

The Twiss House as it appears, overgrown and ivy clad, in the early years of the 21st century

Local survivors who still remember the Twiss mansion in all its glory, regret its destruction. The house dominated the landscape to the south west of Birdhill Village. Three avenues lined with trees and flowers led to the hilltop. The line of the avenues can still be traced. The main entrance was from the village with a lodge guarding an impressive gateway (where Bourkes now reside). The second entrance was through a gateway near Cleary’s Cross (now Hassett’s farm entrance). The third was just a walking path which led to the N7 at Madden’s Turn. The gardens were beautifully manicured and a fish pond was located at the rear of where Clancy’s house is situated. There was also a glass house which contained plants from many countries and a tennis court served as a place of recreation for the family and their many visitors. The landed gentry of those days socialised extensively. Horse drawn carriages conveyed them to each other’s houses in the 19th century. Twiss was the first to introduce a car to Birdhill around 1915. The Goings, with whom the Twiss family socialised a lot, soon had a motor on the road also, registration number FI 4.

Locals had the opportunity of viewing the Twiss residence and gardens at the Field Days which were held occasionally on the grounds to help raise funds for the local school. Up to 10 people were employed in the house and grounds. Among the employees before the house was burned were Hughes, the butler, Warren, the gardener, who lived in Greene’s cottage at the top of Twiss Hill, Martin Ryan, Michael Cahill, the chauffeur who was one of the founding members of the Birdhill Hurling team and attended Board meetings on behalf of the club. The old barracks in Birdhill (now Browsers) which was owned by Twiss up to 1905 was used as accommodation for some of the servants and it was the scene of a number of dances organised for them. The Twiss family bought all their requirements in local shops and farmers sold them fowl, eggs, fish and farm produce. Obviously, they related well with local people but the gentry were generally treated with great respect and, perhaps, with a certain amount of awe, if not fear. They are of an era far removed from what the present generation of Birdhill people experience. But who is to say if the quality of life is any better.